The first time I ever spoke with Marshall Chapman, she was crying on the other end of the telephone line.

My assignment as a young reporter at the Herald-Journal in her hometown of Spartanburg, South Carolina, was to write about the sudden, tragic death of her friend, singer-songwriter Walter Hyatt, in the ValuJet crash that had just happened in the Everglades near Miami.

“He was the first songwriter I ever knew,” Marshall said that afternoon from her home in Nashville. She and Hyatt had been in the same kindergarten class. She still had the photo.

Hyatt was a folk singer with a jazzy streak who formed Uncle Walt’s Band, a popular Austin trio in the 1970s and 80s that Lyle Lovett counted as friends and a main influence. Also in the band: Spartanburg natives David Ball (later a country music star) and guitarist DesChamps “Champ” Hood.

Marshall knew them all from back in Spartanburg. She was in the ninth grade when she joined her first band, The Townships—led by seventh-grader Champ Hood on guitar and his cousin on banjo. Hood introduced Marshall to Bob Dylan, Leadbelly, Odetta and Robert Johnson.

At the time of the airline crash, Hyatt was returning from Key West where he often gigged, headed for his daughter’s college graduation in Virginia.

In a strange way, Hyatt’s death was a gift to me. I’d give it all back, of course, but writing about the tragedy led me to Marshall’s catalogue of songs and ultimately a long friendship with her.

A legend among Nashville songwriters, Chapman’s new album, Songs I Can’t Live Without, officially arrived on May 15 on her own label, Tall Girl Records. More on this strong new record, her first of other artists’ songs—classics by Leonard Cohen, Carole King, Johnny Cash, Otis Blackwell and even a country-soul version of “He’s Got the Whole World In His Hands” among them—to come a bit later.

Marshall would also become an author and actress. My first foray into her music was It’s About Time… recorded live at the Tennessee State Prison for Women, her album on longtime friend Jimmy Buffett's Margaritaville label. Only Marshall could have done it quite that way.

When I heard her song “Alabama Bad” and the line about a barroom waitress who “laughs when they play ‘Stand by Your Man’,” I realized Marshall was a writer and performer of rare talent, skill and humor. I had to know more about her.

Somewhere South

Born and raised in Spartanburg, South Carolina, to an upper-crust family that owned textile mills, Marshall’s made 14 albums, written two books and for magazines, acted in multiple films, toured extensively on her own, and opened for everyone from the Ramones to John Prine. The artists who’ve covered her songs read like a favorites list: Emmylou Harris, John Hiatt, Tanya Tucker, Irma Thomas, Joe Cocker, and oodles more.

She’s a rock ‘n roll rebel who fronted her own band years before most women dared. Marshall is featured alongside her old buddies Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson, the late Walter Hyatt and others in the Country Music Hall of Fame exhibit, Outlaws & Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ’70s, which runs until mid-February 2021.

Marshall is a storyteller always. My favorite part of her musical memoir, Goodbye, Little Rock and Roller, published in 2003 by St. Martin’s Press, is about her history of hard living, which came into focus after she opened for Jerry Lee Lewis at Atlanta’s Great Southeast Music Hall on New Year’s Eve 1978.

Jerry Lee looked right at her, “his eyes burning with a mixture of tongue-in-cheek danger and mock fear, masking what I can now only imagine was disbelief,” she wrote. “Then he said—and I’ve never forgotten it—'Don’t you burn out now, hon.’ I mean it’s one thing when your mother says, ‘Honey, don’t you think you’d better slow down?’ But when the Killer voices his concern… well now, that’s a whole ‘nother thing.”

Country soul

As a child, Marshall was sent home one day from Pine Street School for singing Elvis Presley’s “Too Much” too loudly in the hallway.

After high school, she left for Nashville and Vanderbilt University. At the time, Nashville was far from the boomtown and tourist draw it is today. A traditional Southern city that reluctantly had learned to carry the mantle of country music, in the early 1970s it drew hippies, artists and some of the country’s best young songwriters.

“I was living in a condemned neighborhood… hanging out with Cowboy Jack Clement, Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter, Willie Nelson, Billy Joe Shaver, and Guy and Susanna Clark, and experiencing all kinds of things I never knew existed back in Spartanburg... I thought I’d died and gone to heaven,” Marshall wrote.

She worked with future master-songwriter Rodney Crowell at TGI Friday’s, which was just down the street from the Exit/In where she and many of her musical friends would later appear.

In her 2010 book of interviews,They Came to Nashville, Marshall talks with Crowell about those days. She also interviews Emmylou Harris about waitressing at a local gay bar and later at a Polynesian restaurant, and listens while Kris Kristofferson revealed the details of his being discovered while a janitor at Columbia Records Studios on Music Row. Marshall even spent three sleepless nights on Willie Nelson’s bus, but you’ll have to read her book to find out what happened.

Her recording career began when she landed a deal with CBS Records in Nashville. Recorded in 1977, her debut album Me I’m Feelin’ Free is still among her best. It puts Marshall’s soulful roots on display and exudes a lyrical maturity well beyond her 28 years of age at the time of its release.

The sultry lead track, “Somewhere South of Macon,” is a lost country-soul classic. Sounding like Dusty Springfield with a drawl, Chapman’s young but seemingly weathered voice portrays the hardscrabble life of a cotton-mill worker’s wife in a fictional place based on her childhood home of Enoree, South Carolina:

I cut my teeth in a cotton mill town, somewhere south of Macon Mama fed me a bottle from a moonshine still to wash down the beans and bacon Papa worked the night shift, Mama worked day Never dreaming one day I’d turn and walk away

Turn and walk away from that cotton mill town

Somewhere south of Macon

CBS Records might have wanted Marshall to become the next Bobbie Gentry (who’d hit No. 1 in 1967 with the Delta-inspired “Ode to Billie Joe”) or Tanya Tucker (who had struck gold with “Delta Dawn” in 1972). But country music wasn’t often gritty in the early 1970s and rock rarely had such twang and soul. Marshall always was destined to be herself.

A soulful beginning

Some of Marshall’s main influences in her young life were her family’s African-American cooks and housekeepers.

“While our maid, Lula Mae Moore, was ironing… She and I would listen to the radio, to stuff like Big Joe Turner. Sometimes I’d slick my hair back and imitate Elvis—and she’d laugh and scream and applaud. See, I didn’t get that kind of response from upstairs, so I’d go get it in the basement,” she told writer and musician Peter Cooper for his first book, profiling Spartanburg musicians such as the Marshall Tucker Band, Hank Garland, Ira Tucker of the Dixie Hummingbirds and Pink Anderson (for whom Pink Floyd was named).

Then there was Cora Jeter, who, as Marshall writes in her memoir, could have been the first black woman to defy the segregated order on Spartanburg’s city buses. One day, Marshall witnessed a white bus driver eyeing Ms. Jeter after she took a seat toward the front. Ms. Jeter glared back, saying: “Drive your bus, man. My feets is tired!”

On February 6, 1956, Jeter took Marshall along to witness an American musical epiphany, as Marshall describes in her memoir:

“The first time I ever heard the name Elvis Presley was the same day I saw him play live. ‘They say he white, but sing like he colored,’ Cora said. … I was seven years old and halfway through the first grade. … I remember Cora taking off her apron and saying, ‘Come on, child, let’s go see what all the fuss is about!’ I’d just walked in from riding my bike home from school.

“When Cora and I arrived at the Carolina Theater that afternoon, there were people milling around all over the place, wide-eyed with excitement… Had I not been with Cora, I probably would have been turned away, too, because the main floor was sold out. The only remaining seats were in the ‘colored balcony.’ … Besides Elvis, there was Justin Tubb [Ernest Tubb’s son], the Louvin Brothers, the Carter Sisters, and Benny Martin.

“When he [Elvis] came on, it was like a big bolt of lightning had struck the Carolina Theater. Cora started screaming and laughing at the same time…. The white girls downstairs were screaming so loud, you could barely hear the music. The whole thing was like a big explosion.”

Sixty years later, that experience would inform the title song on her 2013 album, Blaze of Glory:

I saw Elvis Presley sing in 1956

The world was different then, everything was fixed

When he walked out on stage, it shook us to the core

That colored balcony came crashing to the floor…

in a blaze of glory

Rock ‘n roll girl

In all, Marshall recorded three albums for Epic/CBS, including 1978’s Jaded Virgin, with critically acclaimed performances and songs, but production by Al Kooper (of Bob Dylan’s band among many others) that now seems dated in places. Then came the more straightforward rock album Marshall in 1979, which included a remake of “Why Can’t I Be Like Other Girls?,” a signature song originally on Jaded Virgin.

In 1982, Marshall released Take It On Home on Rounder Records, filled with more great songs and a stripped-back sound that sounded more like her. She started writing with Jimmy Buffett in Key West. Four of their songs appeared on his 1985 album Last Mango in Paris. She joined his band officially for 1987 and began to see many of her songs recorded by other artists.

Marshall also began to record more albums on her own terms. 1987’s Dirty Linen (the first release on her own Tall Girl Records) included the gritty “Daddy Long Legs,” later recorded by Tanya Tucker.

In 1991, Marshall released the roots-rock album Inside Job, which she produced with guitarist James Hollihan Jr., who worked for many years with gospel singer Russ Taff. Stereo Review named Inside Job its album of the month in April 1992. Many of the songs later were recorded by other artists, including “Better Off Without You” by Emmylou Harris, “You Can’t Run from Yourself” by Tanya Tucker, and others by the likes of Dion and Wynonna.

Then came It’s About Time…, the live album recorded at the women’s prison, on which Marshall plays her rocker “Bizzy Bizzy Bizzy” from Take It On Home. During the concert, she jokes with the women in the audience how she’d turned down an invitation from Elvis Presley to perform with him that very night at The Pyramid in Memphis.

“I’m sorry E… but I’ve got a show to do that means the world to me!” Marshall says, her voice breaking, and the women roar.

With the live prison album, Marshall made headlines in Time magazine and drew more critical acclaim, but her sales never seemed to match the reviewers’ enthusiasm. I first met Marshall in 1996, when she’d just released Love Slave, one of her three records she co-produced with veteran Buffett band leader Michael Utley. That fall, I saw Marshall play Farm Aid in Columbia, South Carolina, with her full band (the Love Slaves!), followed later in the day by Neil Young, Willie Nelson, Pearl Jam and others.

In 2003, Oxford American featured Marshall’s autobiographical “Leaving Loachapoka” (showcasing singer Ashley Cleveland) in the annual music issue and companion CD:

Driving 90 miles an hour with her hair on fire

Running on a tank full of burning desire

She’s heading out Old Highway number 29

Leaving Loachapoka, Alabama behind

2010 was a banner year for Marshall. She released her second book, They Came to Nashville, a new album Big Lonesome (which The Philadelphia Inquirer called the Best Country/Roots Album of 2010), began her acting career, and witnessed the off-Broadway premiere of her musical Good ‘Ol Girls—adapted from the fiction of Lee Smith and Jill McCorkle, featuring 14 songs written by Marshall and Matraca Berg.

On Big Lonesome, Marshall soulfully sings the Cindy Walker classic, “Going Away Party,” which Marshall says has one of the best lines ever written--“Dreams don’t make noise when they die.”

Two years later, she recorded arguably her best album, Blaze of Glory, which includes the stone blues-rocker, “I Don’t Want Nobody.”

In 2019, Oxford American again showcased Marshall in a special issue (with companion CD) that featured musicians from South Carolina. The editor reportedly listened to Marshall’s entire catalogue before choosing one of my favorites— “Guitar Song” from Take It On Home.

Marshall calls it “a love song to my guitar.” With its simple arrangement and rhythm that recalls Waylon’s “Dreaming My Dreams,” Marshall sings:

Sometimes

I find

That there ain’t a thing in this whole wide world

That makes me feel more like a real live girl

Than this guitar…

… and like a fine spirit that mellows with time

This guitar’s a full-bodied burgundy wine

She never runs dry

She pours out the songs,

While I play along

And I hope to heaven my soul goes to her when I die

“I’ve written hundreds of songs over the years, but there’s only a handful I call my lifesavers,” Marshall says. “It’s like, if I hadn’t written that particular song in that particular space and time, I would have died some sort of spiritual death. ‘Guitar Song’ is one of those songs.”

Keeping the lights on

As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold this year, Marshall began livestreaming shows from the Springwater Supper Club & Lounge, a dive down the street from where she now lives. It’s the oldest bar in Tennessee—Jimmy Hoffa once gambled there—and no weapons (or hula hoops) are allowed inside.

Within a month, Marshall had raised more than $5,000 in online tips for the bar’s out-of-work staff.

“Even though it’s closed, they never turn off the neon lights,” she said about Springwater. “I find that comforting somehow.”

During one show there, someone requested “Ready for the Times to Get Better” from Marshall’s first album. With COVID-19, the song had taken on new meaning.

Marshall dedicated a song in another Springwater show to her longtime friend Betty Herbert, who had recently died of natural causes. Just days earlier, Marshall had serenaded her outside her nursing home window.

There are lots of stories about Betty. One night in 1980 at a club called Cantrell’s, Marshall was playing with her band (the Road Scholars), with Betty’s son Kelley Looney on bass. At one point, Marshall and Kelley looked out to see Betty dancing on top of a table, swinging her pearls in the air with a bottle of a beer, yelling “Raise hell in Dixie on a Saturday night!”

“I got two songs out of that night,” Marshall said, laughing. “’Betty’s Bein’ Bad’ and ‘Alabama Bad’.” (“Betty’s Bein’ Bad” became a top-five country smash for the band Sawyer Brown in 1986.)

In another Springwater moment, Marshall paid tribute to a friend watching online from Paris, Kentucky—Arthur Hancock, a champion horse breeder who recorded for Monument Records in the early 1970s.

Which led to a great story. In late February, Arthur had brought his wife Staci to Nashville for knee-replacement surgery. During her first physical therapy session, Arthur and Marshall got together to play a few songs. Afterward, they rode together to Centennial Medical Center to pick up Staci.

“Y’all won’t believe who was next to me in physical therapy,” she said, struggling to get into the car.

“John Prine.”

Arthur’s eyes got as big as saucers. Marshall knew Prine well, having opened a bunch of concerts for him in the late 1980s and early 90s, often joining Prine to sing “Paradise” at the close of each show.

“You want to meet him?” Marshall asked. Then with Staci’s blessings, Marshall and Arthur headed inside. After introductions were made, Marshall told Prine about how producer Fred Foster had brought in an aspiring young songwriter—named Kris Kristofferson—to play a song he’d just written called “Help Me Make It Through the Night” for Arthur to consider.

Unbelievably, Arthur passed on the song, saying, “Fred, I don’t need nobody helping me make it through the goddamn night.”

Prine loved the story. As Marshall and Arthur walked away, Prine said with a twinkle in his eye, “’Help Me Make It Through the Night’ don’t need no help.”

Then Marshall turned and said, “I love you, John.”

“I love you, Marshall,” he replied.

Those were the last words John Prine said to Marshall. Six weeks later, he was gone. Prine died on April 7, 2020 at Vanderbilt University Medical Center from complications of COVID-19, devastating those who knew him and those who loved his songs worldwide.

A new chapter

In the winter of 2014-2015, Marshall was ready to hang it up. “I’d been through a lot of trauma and I was just worn out,” she said.

Her mother, Martha Cloud Chapman, had died the day after Marshall’s divorce from longtime partner and husband Chris Fletcher had become final. A week later, Marshall herself nearly died after developing C. diff colitis. She was quarantined for a week at Nashville’s St. Thomas Hospital.

It was others’ songs that helped sustain her during those days: Leonard Cohen’s “Tower of Song,” the Bob Seger road classic “Turn the Page,” some old blues numbers, and “I Still Miss Someone” by Johnny Cash—all of which ended up on Songs I Can’t Live Without.

That was five years ago. Now, she’s even reconnected with her ex-husband, Chris. “It takes a lot for me to write somebody off,” she said, laughing.

Marshall’s also an actress. In the 2015 film Mississippi Grind, she played the blues-singing mother of a drifter-gambler played by Ryan Reynolds. She was asked by the producer to record the Donnie Fritts-Dan Penn soul classic “Rainbow Road” with an up-and-coming young producer named Neilson Hubbard. They hit it off and Hubbard suggested they one day do an album together.

And now they have—joined by musicians Dan Mitchell and Will Kimbrough, who writes and records regularly with Jimmy Buffett (including Buffett’s new record in May 2020) and plays in Emmylou Harris’ Red Dirt Boys.

“Will is the James Brown of Americana music,” Marshall said with a laugh. “I don’t know anybody who works harder than Will.”

Marshall’s new album gives her soulful voice room to breathe. She really shines on Cohen’s sly, mysterious “Tower of Song” and on Cash’s “I Still Miss Someone,” one of her best vocal performances.

“That’s my favorite Johnny Cash song,” Marshall said. “And that line in the second verse—‘but I find the darkened corner’—I love that line.”

The new album ends with, of all things, a gospel song, “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands,” which now seems prophetic. “We had no idea there was going to be a pandemic. Nobody did. But people seem to be drawn to it,” Marshall said of the old spiritual.

“He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” ends with a recitation Marshall wrote while driving to the studio. It was the day of the mass shootings in El Paso and Dayton, and when Marshall saw all the flags at half-staff after she exited I-65 onto Trinity Lane in East Nashville, she had to pull over to the side of the road.

While singing “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” at Springwater one recent afternoon, Marshall ended it with the same humming that she and her bandmates harmonize on in the recorded version.

In fact, African-American influences inform much of Marshall’s music even more profoundly than in much of rock ‘n roll. On perhaps her best song, “Goodbye Little Rock and Roller,” Marshall recalls those early influences that shook her to the core:

She played that guitar all day long

Then put her feelings into song

Then sang her songs for Lula Mae

Who said, ‘Child, you got just what it takes’

We all knew she’d leave somehow

To find the world she dreamed about

She never turned around that day

To see her sister wave to her and say

Goodbye little rock and roller

Gee, it sure was good to know you

Goodbye my little rock and roller

Goodbye

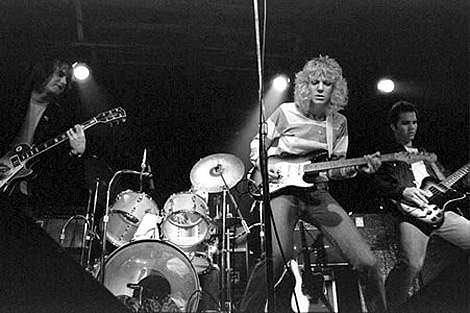

PHOTO GALLERY: A younger Marshall Chapman and her band. Also: Marshall and her guitar, Marshall with Ashley Cleveland and Emmylou Harris, Marshall with Kris Kristofferson, Marshall performing alone, Marshall with Gwyneth Paltrow and Tim McGraw in Country Strong, Marshall performing with Will Kimbrough, and Marshall with her band on the new album: Kimbrough, producer and keyboard player Neilson Hubbard and Dan Mitchell.

Comments